When it comes to water conditions, too much credence is often given to clichés of region as opposed to specific habitats. This includes the notion that African = high pH, hard water and South America = low pH, soft water. Some understand the mistake in this and know that: a) not all African aquatic habitat is highly mineralized, high pH and b) not all SA habitat is low pH and soft water. However, some who understand this still conceptualize SA water conditions as divided along geographic/regional lines that inadequately account for the variations in habitat within the same region.

What's well known to science and not always to hobbyists was proposed by British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace in the 19th century and still holds true today, with some refinement of the details: River water types in SA, though not SA alone, generally fall within the 3 basic types below:

Black water-- This is the soft, low pH, tannin stained water some imagine generally typifies SA habitat and species.

Whitewater-- In order to make things easier on myself while providing a good description, here's a quote from the link to the left:

Clearwater-- Neither tannin stained, nor muddy. Often between the two other types in water parameters, but some clearwater rivers are fairly mineralized/alkaline/higher pH-- or some portions of them are, or some portions of them are during certain times of the year.

The above is very well known in science literature and can also be found in hobbyist literature, such as that authored by Heiko Bleher. It is fundamental to understanding SA fish species and their native habitat and is more important to know and account for with some species than others. Most SA cichlid species adapt reasonably well to non-native water conditions-- within reason and within a certain range-- with the following general exceptions:

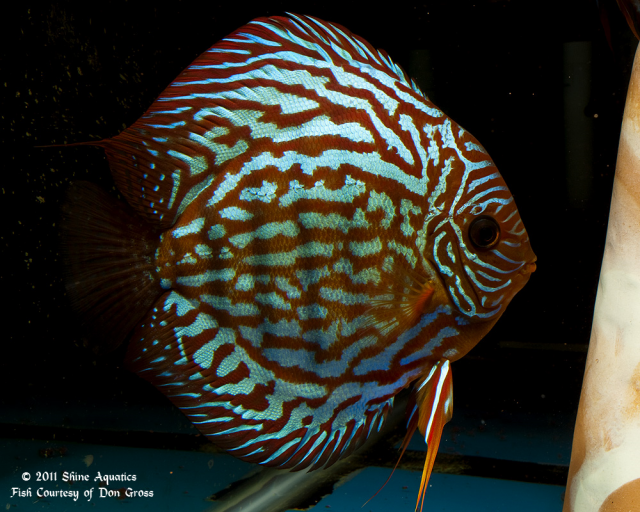

Temperature: Even the normal variation of wild-native temperatures stress some species. For example, surprising to many would be to know that some discus see temperatures in the low-mid 70s in nature, those in such habitats live with this but tend to be stressed when they see such seasonal conditions. Others, like many gymnogeophagus, are well adapted to fairly wide temperatures swings and even need the seasonal variation to maintain good health. The bottom line is temperature is important.

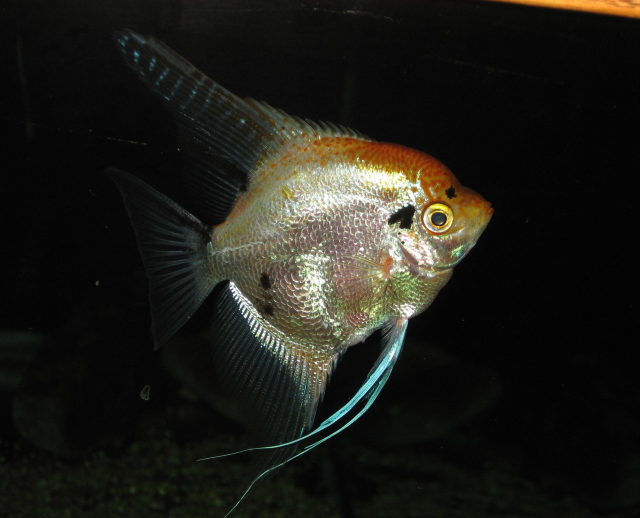

Breeding-- Some species that can live just fine and without issue in higher or lower than native pH or mineralization, may nonetheless be less fecund, or even have difficulty reproducing at all. Here's an example:

Sensitive species-- In varying degrees, some are simply more adaptable to dissolved solids/pH/hardness outside of native conditions than others. A few years ago, through an unintended mistake in one tank, I discovered red head tapajos geos are far more high pH/high alkalinity tolerant than Guianacara (sold to me as G. sphenozona). I 'mysteriously' lost a couple of guianacara before discovering the problem was pH was way higher than I thought. However, the red head geos didn't skip a beat.

The same river sometimes crosses more than one geologic or environmental zone and its water conditions may differ along its length or according to season. For example, some eastern slope rivers originating in the Andes will be harder and higher pH in higher elevations.

Here is another reference, with details slightly different than the one above. There's a good volume of such literature out there, but note that it can vary in the details somewhat, often according to when it was published or when the references it uses were published. This is because greater access in the past couple of decades has resulted in an earlier picture of the waters east of the Andes region being adjusted somewhat. However the basics are the same. (Parenthetical note in the quote below is mine and added for clarification.)

https://www.researchgate.net/public...nce_for_tambaqui_Colossoma_macropomum_culture

So-- if you want to be accurate: SA water habitat is not simply divided between eastern and western slope of the Andes, nor even the Amazon basin vs other regions-- in fact, geologically speaking, it's not that simple either. There are actually several distinct geologic regions east of the Andes or in what we may think of as the Amazon region. A more accurate picture is black water vs clear water vs whitewater, though even at that there can be variation or overlap in pH, hardness, nutrients, and specific mineral profile, including at times variation according to the particular stretch of the river or time of the year. Naturally, something similar can be said of lakes or reservoirs in the region

What's well known to science and not always to hobbyists was proposed by British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace in the 19th century and still holds true today, with some refinement of the details: River water types in SA, though not SA alone, generally fall within the 3 basic types below:

Black water-- This is the soft, low pH, tannin stained water some imagine generally typifies SA habitat and species.

Whitewater-- In order to make things easier on myself while providing a good description, here's a quote from the link to the left:

When a river transports large quantities of sediments it is usually rendered “muddy,” a color somewhat similar to coffee with milk. Major tributaries with headwaters in the Andes are all turbid because of the huge amount of loose material in the high mountain chain that is easily eroded and then carried downstream as far as the Atlantic Ocean. Locally, these rivers are often referred to as whitewater rivers, though the term should not be confused with its English interpretation that can also refer the turbulent waters of rapids. These tributaries include the Madeira, Ucayali, Marañón, Putumayo-Içá and Caquetá-Japurá rivers. There are also several tributaries that do not have headwaters in the Andes but are also considered whitewater rivers because of their relatively high sediment loads, such as the Purus and Juruá. Whitewater rivers have a higher nutrient content than the blackwater and clearwater rivers. The pH of water in turbid rivers is often near or above neutral (7.0). At elevations higher than approximately 2,000 m in the Andes, the pH of river water can be above 8.0.

Clearwater-- Neither tannin stained, nor muddy. Often between the two other types in water parameters, but some clearwater rivers are fairly mineralized/alkaline/higher pH-- or some portions of them are, or some portions of them are during certain times of the year.

The above is very well known in science literature and can also be found in hobbyist literature, such as that authored by Heiko Bleher. It is fundamental to understanding SA fish species and their native habitat and is more important to know and account for with some species than others. Most SA cichlid species adapt reasonably well to non-native water conditions-- within reason and within a certain range-- with the following general exceptions:

Temperature: Even the normal variation of wild-native temperatures stress some species. For example, surprising to many would be to know that some discus see temperatures in the low-mid 70s in nature, those in such habitats live with this but tend to be stressed when they see such seasonal conditions. Others, like many gymnogeophagus, are well adapted to fairly wide temperatures swings and even need the seasonal variation to maintain good health. The bottom line is temperature is important.

Breeding-- Some species that can live just fine and without issue in higher or lower than native pH or mineralization, may nonetheless be less fecund, or even have difficulty reproducing at all. Here's an example:

The researchers recorded the reproductive success of 322 couples, trying out three different combinations: two Rio Negro fish, two Amazon fish or a mixed couple. All aquariums were filled with water from the Rio Negro river. The results were clear (see figure below), fish from the Rio Negro has a higher reproductive success compared to the other combinations. There seems to be some degree of reproductive isolation between the two lineages.

What could have caused the lower spawning rate in the Amazon fish? The researchers think that these fish probably suffered from physiological issues in the black water (remember that all aquariums were filled with Rio Negro water). This water has a lower pH compared to the clear Amazon water. Rio Negro fish are adapted to this pH, Amazon fish are not. It would be interesting to see the results if the couples were swimming in white water. Would the Rio Negro fish then show lower reproductive success?

Sensitive species-- In varying degrees, some are simply more adaptable to dissolved solids/pH/hardness outside of native conditions than others. A few years ago, through an unintended mistake in one tank, I discovered red head tapajos geos are far more high pH/high alkalinity tolerant than Guianacara (sold to me as G. sphenozona). I 'mysteriously' lost a couple of guianacara before discovering the problem was pH was way higher than I thought. However, the red head geos didn't skip a beat.

The same river sometimes crosses more than one geologic or environmental zone and its water conditions may differ along its length or according to season. For example, some eastern slope rivers originating in the Andes will be harder and higher pH in higher elevations.

Here is another reference, with details slightly different than the one above. There's a good volume of such literature out there, but note that it can vary in the details somewhat, often according to when it was published or when the references it uses were published. This is because greater access in the past couple of decades has resulted in an earlier picture of the waters east of the Andes region being adjusted somewhat. However the basics are the same. (Parenthetical note in the quote below is mine and added for clarification.)

https://www.researchgate.net/public...nce_for_tambaqui_Colossoma_macropomum_culture

In the Amazon, there are three main water types (Sioli 1984): muddy (white) waters with a pH range of 6.2 to 7.2 and rich in nutrients, black waters with a pH range of 3.8 to 4.9 and poor in nutrients and clear waters ranging in pH from 4.5 to 7.8. Tambaqui are found mainly on the Solimoes/Amazon and Madeira axis, muddy water rivers systems (Ara˙jo-Lima and Goulding 1997). Because of its migratory nature, for feeding as well as for reproduction, the species can adjust physiologically to the different water types.

So-- if you want to be accurate: SA water habitat is not simply divided between eastern and western slope of the Andes, nor even the Amazon basin vs other regions-- in fact, geologically speaking, it's not that simple either. There are actually several distinct geologic regions east of the Andes or in what we may think of as the Amazon region. A more accurate picture is black water vs clear water vs whitewater, though even at that there can be variation or overlap in pH, hardness, nutrients, and specific mineral profile, including at times variation according to the particular stretch of the river or time of the year. Naturally, something similar can be said of lakes or reservoirs in the region

Last edited: